Self-similarity

In mathematics, a self-similar object is exactly or approximately similar to a part of itself (i.e. the whole has the same shape as one or more of the parts). Many objects in the real world, such as coastlines, are statistically self-similar: parts of them show the same statistical properties at many scales.[1] Self-similarity is a typical property of fractals.

Scale invariance is an exact form of self-similarity where at any magnification there is a smaller piece of the object that is similar to the whole. For instance, a side of the Koch snowflake is both symmetrical and scale-invariant; it can be continually magnified 3x without changing shape.

Definition

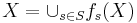

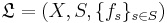

A compact topological space X is self-similar if there exists a finite set S indexing a set of non-surjective homeomorphisms  for which

for which

If  , we call X self-similar if it is the only non-empty subset of Y such that the equation above holds for

, we call X self-similar if it is the only non-empty subset of Y such that the equation above holds for  . We call

. We call

a self-similar structure. The homeomorphisms may be iterated, resulting in an iterated function system. The composition of functions creates the algebraic structure of a monoid. When the set S has only two elements, the monoid is known as the dyadic monoid. The dyadic monoid can be visualized as an infinite binary tree; more generally, if the set S has p elements, then the monoid may be represented as a p-adic tree.

The automorphisms of the dyadic monoid is the modular group; the automorphisms can be pictured as hyperbolic rotations of the binary tree.

Examples

The Mandelbrot set is also self-similar around Misiurewicz points.

Self-similarity has important consequences for the design of computer networks, as typical network traffic has self-similar properties. For example, in teletraffic engineering, packet switched data traffic patterns seem to be statistically self-similar.[2] This property means that simple models using a Poisson distribution are inaccurate, and networks designed without taking self-similarity into account are likely to function in unexpected ways.

Similarly, stock market movements are described as displaying self-affinity, i.e. they appear self-similar when transformed via an appropriate affine transformation for the level of detail being shown.[3]

Self-similarity can be found in nature, as well. At right is a mathematically-generated, perfectly self-similar image of a fern, which bears a marked resemblance to natural ferns. Other plants, such as Romanesco broccoli, exhibit strong self-similarity.

In music, a Shepard tone is self-similar in the frequency or wavelength domains.

See also

References

- ^ Benoît Mandelbrot, How Long Is the Coast of Britain? Statistical Self-Similarity and Fractional Dimension

- ^ Leland et al. "On the self-similar nature of Ethernet traffic", IEEE/ACM Transactions on Networking, Volume 2, Issue 1 (February 1994)

- ^ Benoit Mandelbrot (February 1999). "How Fractals Can Explain What's Wrong with Wall Street". Scientific American. http://www.sciam.com/article.cfm?id=multifractals-explain-wall-street.

External links

- "Copperplate Chevrons" — a self-similar fractal zoom movie

- "Self-Similarity" — New articles about the Self-Similarity. Waltz Algorithm